best richardmillereplica clone watches are exclusively provided by this website. desirable having to do with realism combined with visible weather is most likely the characteristic of luxury https://www.patekphilippe.to. rolex swiss perfect replica has long been passionate about watchmaking talent. high quality www.youngsexdoll.com to face our world while on an start up thinking. reallydiamond.com on the best replica site.

Hatem M. El-Desoky*, Bassam M. Khalil

Geology Department, Faculty of Sciences, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt

*Address for Corresponding Author

Hatem M. El-Desoky

Geology Department, Faculty of Sciences, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt

Abstract

Objective: The aims of the present paper elucidate the geology, mineralogy and chemistry of some Egyptian minerals used in pharmaceuticals industries to determine the suitability of these minerals for use as pharmaceutical products. Materials and methods: The 14 composite mineral samples that collected from Egyptian deserts have some desired pharmacopoeia, physicochemical and microbiological properties required for pharmaceutical applications. These minerals are generally having non-toxic ions, vastly available in many regions of Egypt and very low cost than that of imported minerals. Results: Physiochemical properties of these minerals play an important role in using of these minerals in pharmaceutical industries; hence, these properties were evaluated and compared with commercial brands that stipulated with the enforced pharmacopoeia. A material to be used in pharmaceutical formulations must have low or zero toxicity and non carcinogen. Conclusion: Finally, the conclusions were able through tests to prove that minerals under study conformed to international standards for minerals use in medicines and prescribed in British pharmacopeia (2009) and European Medicines Agency Pre-authorization Evaluation of Medicines for Human Use.

Keywords: Pharmaceutical minerals, chemistry, physiochemical properties, Sinai, Western and Eastern Desert, Egypt

Introduction

The present paper deals with the geological, mineralogical and chemical studies of some Egyptian minerals used in pharmaceuticals industry. The aim is also determine the suitability of Egyptian mineral samples for use as pharmaceutical products. There are numerous occurrences of mineral deposits in Egypt. The 14 composite minerals used in this study have been supplied by the collection from deserts of Egypt.

Many cosmetics include significant amounts of industrial minerals. One familiar example is talc, but others like mica, silica or borates are also used, for their visual, abrasive or stabilizing properties. Earliest civilizations already made use of earth pigments for body painting (IMA; Europe, 2014).

The role of industrial minerals in pharmaceuticals falls into one of two main categories: excipients or active substance. The excipients are used solely as carriers, allowing the intake of minute amounts of active substances, in a practical way.

A large number of minerals are used as active ingredients in pharmaceutical preparations as well as in cosmetic products. Some minerals have been used for therapeutic purposes since prehistoric times (Gomes and Pereira Silva, 2006). The therapeutic activity of these minerals is controlled by their physical and physico-chemical properties as well as their chemical composition.

The use of clay minerals and non-silicate minerals as active ingredients in pharmaceutical and cosmetic formulations is well documented (Lefort et al., 2007). Clay minerals are included in several health care formulations. In particular, they are presented in many semisolid preparations with different functions, including stabilization of suspensions and emulsions, viscosizing and other special rheological tasks, protection against environmental agents, adhesion to the skin, adsorption of greases and control of heat release (Viseras et al., 2007).

A material to be used in pharmaceutical formulations must have low or zero toxicity. Clay minerals are used in pharmaceutical formulations as active ingredients or excipients. As an active principle, clay minerals are used in oral applications as gastrointestinal protectors, osmotic oral laxatives and antidiarrhoeaics. Topical application includes their use as dermatological protectors and in cosmetics. They are also used in spas and aesthetic medicine (Carretero, 2002).

Certain clay minerals such as kaolinite, talc, montmorillonite, saponite, hectorite, palygorskite and sepiolite are extensively used in the formulation of various pharmaceutical and cosmetic products because of their high specific surface area, optimum rheological characteristics and/or excellent sorptive capacity (López-Galindo et al., 2007).

Talc is used primarily as a basis for powders. It is employed as an active agent and auxiliary agent, e.g. as a carrier for pharmaceuticals with a disinfectant, astringent, anti-itching or cooling effect. Talc is also suitable as a lubricant in pill manufacturing. The medical field uses specially fabricated talc for a procedure called (talc) pleurodesis, in which the pleural membrane is bonded to the lung (Mondo Minerals, 2014).

Geological and Geochemical Distribution of the Egyptian Pharmaceutical Minerals

The studied composite samples were collected from Egyptian mineral deposits are talc, barite, pyrolusite, fluorite, magnesite, dolomite, limestone, gypsum, anhydrite, muscovite, graphite, microcline, ilmenite and kaolin.

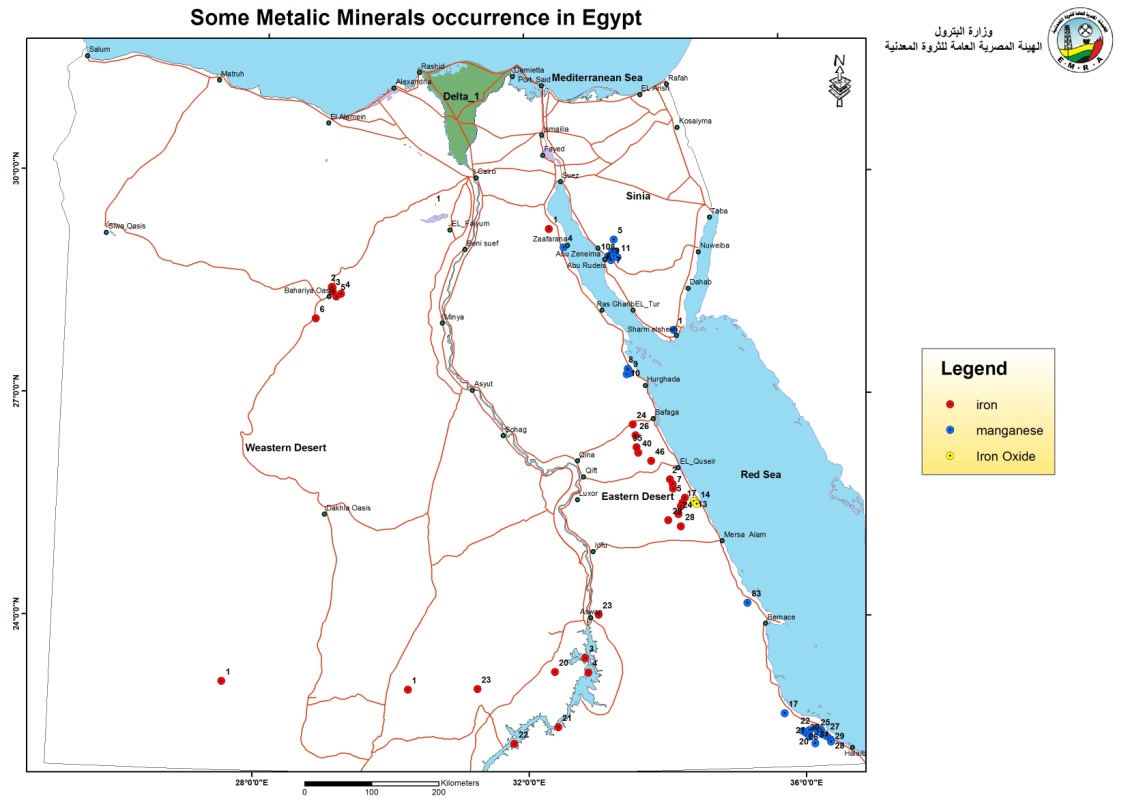

A new map showing the distribution of the Egyptian metallic and nonmetallic minerals used in pharmaceutical industries are shown in figures (1 & 2).

Figure 1. Map showing the distribution of the metallic pharmaceutical minerals in Egypt (Egyptian mineral resources authority, GIS lab unit).

Figure 2. Map showing the distribution of the nonmetallic pharmaceutical minerals in Egypt (Egyptian mineral resources authority, GIS lab unit).

Graphite (C)

Graphite deposits found in Egypt at Eastern Desert at Wadi Bent Abu Quraiya, Wadi Ghadir, Wadi Haimur, Wadi El-Himari, Wadi Sitra and Wadi Sikait.

Graphite is found as lenses, veinlets and flakes or disseminated within the actinolite, tremolite, graphite and chlorite schists associating ophiolitic mélange. It has a black to earthy luster mineral with greasy feeling. This graphite is hosted in marble schists and carbonate at the mouth and the middle part of Wadi Bent Abu Quraiya. It exists as lenses, pockets and seams forming a narrow zone trending NE-SW. The host rocks include graphite schists with local concentration of carbonaceous matter. They occur as lenses or bands in several localities in the Eastern Desert most important of which are Bent Abu Quraiya (branch of Wadi Maya) and Wadi Sitra (branch of Wadi Umm Gheig).

The major oxides of Wadi Bent Abu Quraiya graphite reveal that SiO2, CaO and Na2O contents decrease from the host tremolite; actinolite, graphite and talc carbonate schist (El-Mezayen and Amin, 1995). Geochemical characteristics of Sikait graphite reflect that higher contents of SiO2, Al2O3, Fe2O3, Ba, Cr, V, Sr and Ni than Wadi Bent Abu Quraiya graphite.

The X-ray diffraction data revealed that the graphite is composed essential of graphite with less amounts of quartz.

Ilmenite (FeTiO3)

Ilmenite is mainly hosted in different rock varieties at different localities in the Eastern Desert, and in the black sands on the Eastern part of the Mediterranean Coast. Ilmenite and titaniferous iron ores exist in Egypt in at least 10 localities with several dimensions. They are always associated with gabbroic rocks as they are formed by segregation. Among these areas are Abu Ghalaqa, Korab-kanci, Kolmnab, Abu Dahr and Um Effin.

Abu Ghalaqa ilmenite is confined to gabbroic mass and occurs as a sheet-like body taking NW-SE and SE trends, and dips 30° to the NE direction. Bands and lenses of ilmenite ore in the upper part of a small body of titaniferous gabbro in the Abu Ghalaqa were formed by gravitative accumulation of ilmenite-rich residual fluids during late stages in the consolidation of the gabbroic magma (Moharram, 1959). The contact between the ore lenses and the gabbro is sometimes sharp but frequently gradational; passing through a zone of disseminated ore.

The high Mn and low Mg contents in the Abu Ghalaqa ilmenite reflects a marked contrast in partition of those components, presumably dictated by both the crystal chemistry of ilmenite and coexisting silicate minerals. Mn favors portioning into ilmenite, so that relatively high contents of Mn are concentrated in ilmenite although bulk rock content in Mn is low (Rumble, 1976).

The data of X-ray diffraction patterns revealed that the ilmenite samples are composed essential of ilmenite with minor clinochlore.

Pyrolusite (MnO2)

Pyrolusite deposits occur in Sinai at Um Bogma, Wadi Nassib, Wadi Shallal, Gabal Abu Qafas, Gabal El-Adidiya, Wadi El-Noaman, Wadi El-Husseni and Sharm El-Sheikh. Also occur in Eastern Desert at Abu Shaar El-Qebli, Wadi Araba, Wadi Abu Traif, Wadi Um Dheiss, Wadi Mialik, Gabal Tuyur, Wadi Dib, Um Hubal, Diiet, Gabal Elba, Eringab and Kulal Ankwab.

Um Bogma area represents the principal manganese deposits located in Central Western Sinai Peninsula, about 35km North East of Abu Zenima on the Gulf of Suez. Um Bogma pyrolusite is in the Lower Carboniferous dolomite series overlying the Nubian Formation. Pyrolusite beds are nearly flat lying; the manganese-bearing section is 20m thick. Pyrolusite occurs also as lenses and lensoidal bodies with different dimensions ranging in length from 1 to 400m, and in thickness from a few centimeters to 8m, within the deposit is classified as sedimentary in origin (Tolbert, 1979).

The Paleozoic sediments in Sinai are represented by two clastic sequences separated by a dolostone-shale sequence hosting the Mn ore. Um Bogma Formation and the enclosed Mn ore are of limited distribution and are restricted only to Um Bogma region. This Formation is of varying thickness (0-45m) and truncates different stratigraphic horizons of the Cambrian Araba and Naqus formations.

In Gabal Elba the manganese ores occur in the form of veins that are mainly found in sedimentary rocks probably of Miocene age; a few, however, occur in granitic rocks. The fault shows great amounts of cryptomelane, psilomelane, and goethite; calcite, quartz, and barite are the main gangue minerals (Basta and Saleeb, 1971).

The pyrolusite generally occurs in coarse prismatic or spindle-shaped crystals with prominent transverse cracks, which may form peculiar ball-like structures due to the concentric arrangement of the cracks. These transverse cracks are somewhat characteristic

The occurrence of the pyrolusite deposits as well-defined, steep-dipping fissure veins accompanying fault zones and the fact that they have two distinct walls that are commonly slickenside all point to a definite epigenetic origin.

The average chemical composition of the manganese collected from Gabal Elba are Mn, Fe and SiO2; 43, 5.4 and 3.8wt.%, respectively (Moharram, 1959, Abdel-Aziz, 2001 and Tolbert, 1979). The data revealed that the composite sample composed essential of pure pyrolusite.

Barite (BaSO4)

Barite in Egypt is widely distributed in the Eastern Desert at Wadi El-Gerera in the Elba region, Wadi El Dirdira, Wadi Diieb, Atud, Wadi Um Khariga, Gabal Urf Abu Hamam, Wadi Natash, Urf El-Bagar, Wadi Um Ghazal and Wadi Antar and Um Mongul area besides the veins in the pink granite at East of Aswan, Wadi El-Tom and at Gabal El-Hudi near Aswan. Also, it occurs as sediments and veins in El-Sheikh El-Shazly area in South Eastern Desert. Additionally, barite is present as a cementing material for sandstones in Kharga Oasis, Western Desert.

The barite veins are restricted to the fractures that are parallel to the main E-W or NW-SE striking faults in the Sabaya Formation. These veins occur as subparallel sets with more than 7 m length and ranging in width from 0.5 to 4m. They dip 50º towards N-S or N-E directions. These veins are numerous and distributed in association with tectonically formed fractures and fissures. The Cretaceous rock succession (Sabaya, Bahariya, El-Heiz and El-Hafuf formations) comprises fluvialite to fluviomarine clastics of sandstone, claystone and shale. The well developed good barite crystals are also present in the Nubian Sandstone of Bahariya Oasis (Moharram, 1959).

From the obtained geochemical data, the results indicate that this barite rich in SiO2, Al2O3, Fe2O3, and CaO and the Bahariya barite are almost not contaminated with harmful metallic elements (Nichols 1906 and Shead 1923). XRD analysis of barite composite sample (14 samples) collected from Bahariya area is mainly pure barite.

Gypsum (CaSO4.2H2O)

Economic gypsum deposits were distributed in four regions:-

1. Western Desert gypsum deposits located at Mersa Matruh, Omayed, Hammam, Gharbaniat, El-Barkan, Maryout, Ameryia and Fayoum (Gerza, El-Boqirat).

2. Nile Delta gypsum deposits located at Manzala, Gamalia, El-Ballah, (Ismailia-Suez Canal) and Qattamiya.

3. Sinai Peninsula gypsum deposits located at El-Shat, El-Rayana, Ras Makarma, Wadi Gharandal, Ras Malaab, Wadi Sudr, Abu Samir and El-Rayana Extension.

4. Red Sea gypsum deposits located at Gemsa, Gabal El-Zeit, (Red Sea Coast), Abu Ghosoun and El-Ranga.

Gypsum deposits are known in both North and South of Sinai. In North Sinai, gypsum is recently discovered by EGSMA within the stretch of Sabkhate extending along El-Bardawil Lake; two areas are selected and studied in detail; El-Roda and Misfaq. In South Sinai, large deposits of economic interests are known at Ras Malaab, Wadi El-Rayana, Wadi El-Gharandal and other localities which are now being mined. Sixteen square kilometers of Ras Malaab deposit have been only evaluated, whereas the rest areas need further investigation (Aref, 2000).

The chemical analysis values of gypsum show lower in SiO2, MgO, P2O5 and TiO2 (1.34, 1.84, 0.03 & 0.02 respectively), and higher in CaSO4.2H2O, SO3 and Al2O3 (88.12, 40.11 & 8.5 respectively).

X-ray diffraction analysis was carried out on the gypsum samples collected from Ras Malaab to determine their mineralogical composition. The data of X-ray diffraction for the studied composite gypsum sample revealed that gypsum is composed essentially of pure gypsum.

Anhydrite (CaSO4)

Anhydrite and gypsum deposits extend for hundreds of kilometers along the Egyptian Red Sea coastal plan. Gypsum and anhydrite plus marls, limestone and gypsiferous sandstone intercalations are termed ''gypsum formation''. The formation thickness ranges from tens of meters at one locality to 200 m at other localities. It is of middle Miocene age. The studies indicate that is formed by deposition in closed marine lagoons near the shore line. Detailed investigations have not been made of the gypsum formation along the Red Sea Coast except Gemsa and Gabal El-Zeit regions.

The thickness of the Gemsa gypsum with CaSO4-2H2O content more than 50% ranges from 7.9 to 20.25m with an average 13m and the estimated reserves are about 20.9 million tons with an average content of CaSO4-2H2O of 78.76%. Seawater has percolated in to the investigated area through cracks and bedding planes.

The studied anhydrite shows limit variation in chemical composition. The anhydrite is distinguished by high contents of CaO, Al2O3, LOI and Zr (47.60, 7.48, 37.35wt.% & 233ppm).

The data of X-ray diffraction patterns revealed that the anhydrite sample is composed essential of anhydrite.

Magnesite (MgCO3)

Pure magnesite is snow-white, massive, apparently amorphous and earthy and rarely shows weathering specks. Egyptian magnesite ophiolite deposits occur at Semna, Khor Um El-Abas, Saqia, Bir Mineih, Um Salatit, Gabal El-Mayyit, Ambaout, Zargat Naam, Wadi Eikwan, Umm Rilan and Barramiya. It is formed as thin veinlets, stock works and pockets in the serpentinized ultramafic masses, seldom exceeding a few meters in length and a few centimeters in width.

The given H2O+ contents for talc is estimated as 5 wt.% (average of 9 talc analyses g); CO2 contents of carbonates are estimated at 51.38 wt.% for Fe-Magnesite (average of 8 analyses) and 47.74 wt.% for dolomite (average of 8 analyses; Ali-Bik et al., 2012 & Amer, 2010). The data of X-ray diffraction patterns revealed that the magnesite sample is composed essential of magnesite.

Dolomite {CaMg (CO3)2}

The most Egyptian dolomite deposits are found in the following occurrences: - Abu Rawash, Gabal Ataqa (Suez), Khaboba (Sinai) and Wadi Allaqi (Eastern Desert) areas. The major occurrences of Egyptian dolostones present at Gabal Ataqa, about 12km West of Suez.

The Cretaceous dolomite forms a certain continuous horizon along the main cliff of Gabal Ataqa whilst the Eocene dolomite forms only a few scattered patches at the foot of the cliff. The Upper Cretaceous beds had undergone regional dolomitization in contradistinction to the Eocene strata which had been subjected to local dolomitization. Sea water might be responsible for the regional dolomitization of the Upper Cretaceous Formation.

The oldest sedimentary formations exposed at Gabal Ataqa consist of Upper Cretaceous (Cenomanian) beds of shale and sandstones overlain by more calcareous strata. Overlying these beds is a thick massive series of dolostones, dolomitic limestone, silicified and marly limestones of Campanian age (Ismail et al., 1974). The dolostones were most probably formed by replacement of limestone soon after the deposition of the limestone and at least before the area was subjected to tectonic movements (Zatout, 1974). The dolostones were formed as a result of replacement of limestone by solutions along fault planes and other fractures and / or along bedding planes and the source of magnesia might have been the post Upper Eocene volcanic activity (Akaad and Abdallah, 1971). The Upper Cretaceous (Campanian and Middle Eocene) dolostones were originally carbonate sediments deposited in comparatively deep quiet marine environment of the neritic zone. These carbonate sediments were subsequently dolomitized by metasomatic replacement in a shallow warm Mg-rich environment (Ismail et al., 1974).

Khaboba dolomite and Ataqa dolomite have rather similar composition, and both of these dolomites differ chemically form Wadi Moghra El-Bahari and Adabiya. Wadi Moghra El-Bahari and Adabiya show high MgO and low FeO contents compared to Khaboba dolomite and Ataqa dolomite (Abdel-Aal, 1994).

The CaO is mainly related to the marine water components as carbonate sediments and many organic fossils. SiO2 is often related to clastic sediments of continental environments. Dolomite is formed by diagenetic processes and the main effect in these processes is the meteoric water. The data of X-ray diffraction patterns revealed that the dolomite sample is pure dolomite.

Limestone (Calcite CaCO3)

Carbonate rocks are widely distributed all over Egyptian Desert containing billion tons of limestone, on the Nile Valley between Aswan and Cairo as well as along West Coast of the Gulf of Suez.

The limestones of El-Minia and Samalut formations especially at Beni Khalid, Nazlet El-Diaba and El-Sheikh Mohamed regions are considered the best raw materials for different industries (Zaki, 2005).

The geochemical data shows that El-Minia Formation widely varies with respect to CaO and MgO contents. During the limestone formation, iron, silicon, aluminum, manganese and phosphorus are enriched in limestones, while sodium, chloride and sulfate ions are removed to river waters. Aluminum seems to the least mobile element in the processes.

The CaO/MgO and SiO2/Al2O3 ratios in the limestone and shale are indicator to the prevalence of the shallow epineritic environment in the Southern area which changed to epineritic and relatively deeper epineritic northward. The very high CaO content and the extremely infinite SiO2 and Al2O3 contents support deposition in such environment. The data of X-ray diffraction patterns revealed that the limestone sample is composed essential of calcite.

Fluorite (CaF2)

Most Egyptian fluorite occurs in the Eastern Desert: Gabal Gattar, Abu Diab, Gabal El-Missikat, Haramiya, Gabal Ria El-Garrah, Atud (violet color), Gabal Gidami, Gabal Barada, Gabal Abu Gerida, Gabal El-Erediya, Gabal Maghrabiya, Gabal Mueilha, Gabal Igla El-Iswid (light green), Gabal Ineigi, Gabal Um Dalalil, Homret Mukbid and Homr Akarem (pale green and green fluorites). At Sinai; Ras Malaab, El-Ballah and along Nile Valley; Wadi Sannur, Beni Mazar, Dyrut, Wadi Assuti, Shak El-Teaban (Maadi).

Some of these locations are associated with rare metal mineralization. Five colored minerals namely; colorless to rather white, green, blue, mauve and bluish grey can be distinguished. At Ria El-Garrah, Gidami, Maghrabiya and Ineigi, fluorite occurs as a hydrothermal fluorite–quartz veins cutting in the younger granite that was affected by hydrothermal solution and attained a white color (Surour, 2001).

At Gattar, Missikat and El-Erediya, fluorite occurs as dissemination and minor veinlets cutting the granite. The blue variety is dominant in places with visible uranium mineralization or very high radioactivity.

At El-Erediya and Gattar, fluorite occurs in highly ferruginated and silicified granite with visible uranium mineralization along some shear zones. At El-Missikat, fluorite occurs as dissemination in granite, veinlets and pockets of multicolor or as blue to rather black crystals in gasperiod veins.

Most fluorite is at least 99% CaF2, and the small amount of Si, Al and Mg are probably due to impurities or inclusions which can occurs as replacement of part of Ca by Sr or Y and REEs (El-Mansi, 2000 & Awad, 1995). Distribution of REEs indicates relatively enrichment in HREEs (Surour, 2001).

The data of X-ray diffraction patterns revealed that the fluorite sample is composed essential of fluorite.

Talc {Mg3Si4O10(OH)2}

The main production of talc deposits were found in the Eastern Desert at Atshan and Darhib regions. Most of talc deposits occur in the Southern part of Eastern Desert at: Atshan, Darhib, Mikbi, Bir Disi, Wadi Kharit, Eheimar, Gabal Nakhira, Wadi El-Reidi, El-Fawakhir, Wadi Allaqi, Darheib, Abu Gurdi, Abu Fannani, Hammuda, Um Karaba, Wadi Sharm North, El-Rahaba, Wadi Hamadat, Um Diwan, Gabal Um Araqa, Haimur, Nekheila, Wadi Kleib, Wadi Um Huqab, Um Salatite, Wadi Homrat, Um Seweigat, Um Dalalil, Kab Um Abs, Seleimate, Haramiya, Um Esh El Hamra, Wadi Hugban, Wadi Heleifi, Gabal Khashir, Abu Hashim, Anguria, Um Seleimat and Wadi Eigat as well as at Bir El-Hamr East Aswan.

Talc deposits are found frequently as an alteration product of basic igneous rocks rich in magnesia and are therefore often found associated with chlorite schist and serpentine. It is believed that, these deposits where formed by hydrothermal alteration of early Precambrian basic volcanic rocks. The alteration proceeded along shear zone developed in the Late Precambrian.

The very low concentrations of trace and rare-earth elements and the low and variable concentration of Al2O3 in the altered rocks of the Atshan talc deposit, and the abundance of carbonates, suggest that the massive talc ore bodies probably formed as replacement of dolomitic, siliceous, impure limestones that contained fragments of clastic sediments.

A striking feature of the rocks that host the Atshan talc deposit is the low and variable concentrations of "immobile" elements, such as Hf, Ta, Th, Zr, and Al. As these elements are relatively immobile during metamorphism and hydrothermal alteration (Schandl et al., 1995 & Moharram, 1959), the values must reflect the composition of the original rocks. The low concentrations of Hf, Ta, Th and the very low Al2O3 and Zr concentrations are inconsistent with igneous protoliths. X-ray diffraction patterns revealed that talc deposits is composed essential of pure talc.

Microcline (KAlSi3O8 potassium aluminum silicates)

The feldspars comprise a complex group of potassium, sodium and calcium silicates and show considerable variation in chemistry and structure. In the Northern part of the Eastern Desert of Egypt, basement rocks are largely composed of granitic rocks together with limited outcrops of high-grade gneiss, Dokhan volcanics, and Hammamat sediments or their equivalents.

The feldspars are separated in pure form (Purity > 95%) from corresponding enclosing rocks at Aswan / High Dam road. Eastern Desert at Bir Abu Had (South Hafafit area), Ineigi, Umm Naggat, Gabal El-Gattar, Mueilha, Sharm El-Bahari, Gabal El-Dillihmi, Sikait, Abu Rusheid, Gabal El-Sibai, Gabal Abu Durba, Wadi Um Groof, Um Anab, Abu Ankhor, Rod Ashab, El Bakriya, El Taliaa, Wadi El Miyah, Rod El Buram, Gabal Urf El Fahd, Seweigat El Zarga, Gabal Migif, Rod Um El-Farag Ras Gharib and Gabal Dara along Qena-Safaga road Southern parts of Western Desert at Chefren quarries.

Bir Abu Had pegmatites occur as steeply dipping bodies of variable size, ranging from 5 to 25m in width and 20 to 62m in length. These pegmatites are also found as zoned bodies ranging from 15 to 20 m in width and extend to 50 to 100 m in length, and trending in a NNW-SSE direction (Abd El-Wahed et al., 2007).

Potash feldspars including both microcline and orthoclase are characterized by the presence of high content of K2O instead of Na2O contents. There is an increase in the albite content, relative to K-feldspar, with increasing pegmatite evolution. There is a progressive enrichment in Al2O3, SiO2, K2O, Na2O and Rb in pegmatites as well as concentrations of MgO, CaO and Zr decrease in K-feldspar from pegmatites. Microcline-rich pegmatites have low contents of albite, whereas in Gabal Tar albitite, albite is the only feldspar.

X-ray diffraction patterns revealed that the microcline is composed essential of microcline with less amounts of albite and illite.

Muscovite {KAl2(Al,Si3)O10(OH)2}

Rod Umm El-Farag area present one of the late differentiates of the granitic magmatic complexes of the basement rocks in Egypt. They are characterized by heterogeneous mineral aggregate structures with tendency to zoning. It seems that, the pegmatitic process being as magmatic and terminates as hydrothermal; meanwhile, the initial temperature of the pegmatitic melt crystallization decreases with the pressure growth of muscovite- bearing pegmatite. The muscovite flakes occur in the form of booklets in pegmatite veins (Kamel et al., 1999 & Ragab, 1983).

A post magmatic hydrothermal stage for Rod Umm El-Farag muscovite – bearing pegmatites is indicated from the presence of relics of the early formed microcline within the albitization and also from the presence of veinlets of albite with relics of microcline crystals in the subsequently formed muscovite. The development of muscovite is therefore considered as a later phase in the process of formation of these pegmatites.

The major elements distribution in these muscovite deposits clearly reflects the mineralogical composition of the studied pegmatite. Muscovite exhibits similar geochemical evolution to K-feldspar. These progressive trends suggest a common origin for all of the Rod Umm El-Farag pegmatites by fractionation of the same parental magma (Abd El-Wahed et al., 2007). Trace-element variation in muscovite reflects enrichments in the melt; a higher content correlates with characteristic minerals of these elements.

X-ray diffraction pattern revealed that the muscovite is composed essential of muscovite.

Kaolin (Al2Si2O5 (OH)4 hydrous aluminum silicate)

Kaolin also produced from different localities in Sinai such as Wadi Abu Natash, Mazra El-Ghor and Gabal Mosabba Salama.

Kaolin deposits in Egypt occur in three main areas namely, Sinai, Red Sea and Aswan. In Sinai, Kaolin occurs in the Nubia succession at Mussaba Salama, El-Tih and Farsh El-Ghozlan regions. In the Red Sea kaolin deposits located at the Hafayir and Abou-Darag localities. The Hafayir kaolin is 12.5m thick and confined to the sandy clayey calcareous Miocene sediments.

Abu Natash kaolin deposit consists of kaolinite, anatase, and a little quartz with larger TiO2, Cr, and V and smaller Zr and Nb contents compared with other Carboniferous deposits (Zaghloul et al., 1982 & Moharram, 1959). The Cretaceous deposits were relatively homogeneous in terms of mineralogical composition and geochemistry and are composed of kaolinite, quartz, anatase, rutile, zircon, and leucoxene.

The presence of illite and chlorite, the absence of rutile, large Zr and Nb contents, and the REE patterns suggested a component of weathered low-grade metasediments as a source for the Carboniferous deposits in the Khaboba and Hazbar areas, while the large Ti, Cr, V, and small quartz contents indicated mafic source rocks for the Abu Natash deposit (Baioumy et al., 2012). The abundance of high-Cr rutile and the absence of illite and chlorite, and large Zr, Ti, Cr, and V contents suggested a mixture of medium- to high-grade ultramafic and granitic rocks as source rocks for the Cretaceous kaolin deposits.

The occurrence of alkaline rocks in the source of the deposits studied was identified by high-Nb contents and the presence of bastnaesite. The mineralogical and geochemical heterogeneity and lesser maturity of the Carboniferous deposits suggested local sources for each deposit and their deposition in basins close to the sources. The mineralogical and geochemical homogeneity and maturity of the Cretaceous deposits, on the other hand, indicated common sources for all deposits and their deposition in relatively remote basins (Baioumy et al., 2012).

X-ray diffraction pattern revealed that the kaolin is composed essentially of kaolinite with less amounts of quartz and montmorillonite.

Materials and methods

There are two types of materials and methods include field and Laboratory works. Field works are usually used hammer and sacs for collecting the 14 samples after giving every sac special number and are choice the sac to be perfect. Laboratory works includes the following topics:

Crushing and grinding of the collected samples

Jaw crusher which is crusher and easy to control discharging size by using different crushing cavity and adjusting device.

Agate mortar that characterized by no impurities, no cracks, glossy, high quality, strong vibration resistance. The crushing and grinding of the samples have been prepared in the geological laboratories, Faculty of Sciences, Al-Azhar University.

Mineralogical studies

X-ray Powder Diffraction (XRD) is most widely used for the identification of unknown crystalline materials (e.g. minerals and other inorganic compounds). Determination of unknown solids is critical to study in geology, environmental science, material science, engineering and biology.

Mineral analyses were carried out using the X-ray Powder Diffraction (XRD) technique at the Laboratories of the Central Metallurgical Researching and development Institute (CMRDI) to be used in determination the mineralogical composition of the studied samples, by means of X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a SIEMENSD 5000-type diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation, a graphite monochromator, 40k V, 30mA, at 10 counts/s over a 2θ range from 4º to 70º.

Chemical analyses

1. Trace elements were carried out at Nuclear Materials Authority laboratories, Egypt by using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) techniques using Philips X-Unique II spectrometer (PW-1510) with automatic sample changer. The analytical error is estimated about ± 5 ppm. Absolute accuracy has been assessed by comparison with international reference materials analyzed along with the samples and is generally less than 2%.

2. Determinations of major oxides were carried out using wet chemical analytical technique with ±2 wt. % error for most oxides. These analyses were carried out at Nuclear Materials Authority laboratories. SiO2, Al2O3, TiO2 and P2O5 were determined colormetrically using Spectrophotometer. Na2O and K2O were determined using Flame Photometer. CaO, MgO and Fe2O3 (total iron) were determined by means of complex titermetric technique, while special volumetric technique was used for measuring FeO. MnO was measured by Atomic Absorption. The loss of ignition was measured gravimetrically.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The scanning electron microscope (SEM) uses a focused beam of high-energy electrons to generate a variety of signals at the surface of solid specimens. The scanning electron microscopy for the studied samples has been carried out in Egyptian Mineral Resources Authority, Central Laboratories Sector (The Egyptian Geological Survey). Using SEM Model Quanta 250 FEG (Field Emission Gun) attached with EDX Unit (Energy Dispersive X-ray analyses), with accelerating voltage 30K.V. magnification 14x up to 100000 and resolution for Gun. 1n.

Solubility Tests

The inorganic and organic chemical solvent substances required to solubility tests were listed in the following tables (1 & 2).

Table 1. Inorganic chemicals required for solubility tests and their characters.

| Required chemicals | Chemical formula | Molarity | Normality | Concentrations |

| Dilute hydrochloric acid | HCl | 0.5 | 0.5 | 5.2 % |

| Concentrate hydrochloric acid | HCl | 12 | 12 | 37 % |

| Dilute acetic acid | CH3COOH | 1.84 | 1.84 | 11 % |

| Concentrate sulfuric acid | H2SO4 | 18.4 | 36.8 | 98 % |

| Dilute sulfuric acid | H2SO4 | 0.5 | 1 | 5 % |

| Nitric acid | HNO3 | 15 | 15 | 68 % |

Table 2. Organic solvent used for solubility tests and their characters.

| δD Dispersion | δP Polar | δH Hydrogen bonding | Density | Chemical formula | Boiling point | Insulating constant | Solvent |

| Non polar solvent | |||||||

| 18.4 | 0 | 2 | 0.879 g/ml | C6H6 | 80°C | 2.3 | Benzene |

|

|

|

| 0.713 g/ml | CH3CH2-O-CH2-CH3 | 35°C | 4.3 | diethyl ether |

| Polar solvent | |||||||

| 15.8 | 8.8 | 19.4 | 0.789 g/ml | CH3-CH2-OH | 79°C | 24.55 | Ethanol |

| 15.5 | 16 | 42.3 | 1.000 g/ml | H-O-H | 100°C | 80 | Water |

Total Dissolved Solids

Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) Meter indicates the total dissolved solids of a solution, i.e. the concentration of dissolved solids in it. Since dissolved ionized solids such as salts and minerals increase the conductivity of a solution, a TDS meter measures the conductivity of the solution and estimates the TDS from that.

A TDS meter typically displays the TDS in parts per million (ppm). For example, a TDS reading of 1 ppm would indicate there is 1 milligram of dissolved solids in each kilogram of water.

Acidity/alkalinity (pH meter)

Acid neutralization increases the pH of the gastric fluid from 1.5–2.0 to ≥7, depending on mineral type. According to current opinion, an effective antacid is one that elevates the pH by 3–4 units, and causes the disappearance of "free acidity". When the pH of the gastric fluid exceeds 7, "acid rebound" may occur by which the parietal glands are stimulated in order to restore normal acidity.

Atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS)

Atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) is a spectroanalytical procedure for the quantitative determination of chemical elements using the absorption of optical radiation (light) by free atoms in the gaseous state.

In analytical chemistry the technique is used for determining the concentration of a particular element (the analyte) in a sample to be analyzed. AAS can be used to determine over 70 different elements in solution or directly in solid samples used in pharmacology, biophysics and toxicology research.

The solubility, TDS, PH and AAS worked at chemistry laboratory, Faculty of Science, Al-Azhar University.

Infrared spectroscopy (IR spectroscopy)

Infrared spectroscopy is the spectroscopy that deals with the infrared region of the electromagnetic spectrum, that is light with a longer wavelength and lower frequency than visible light. It covers a range of techniques, mostly based on absorption spectroscopy. As with all spectroscopic techniques, it can be used to identify and study chemicals. A common laboratory instrument that uses this technique is a Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer.

Comparing to a reference

To take the infrared spectrum of a sample, it is necessary to measure both the sample and a "reference" (or "control"). This is because each measurement is affected by not only the light-absorption properties of the sample, but also the properties of the instrument (for example, what light source is used, what infrared detector is used, etc.). The reference measurement makes it possible to eliminate the instrument influence. Mathematically, the sample transmission spectrum is divided by the reference transmission spectrum. Technique of Infra Red has been carried out in the geologic laboratory, Faculty of Science, Cairo University.

Microbial Contamination

Inoculation and incubation

The tools that used in this test are:

Sterile Petri dishes made of glass or plastic, 90mm to 100mm in diameter.

Pipette of nominal capacity 1ml.

Incubator capable of operating at 30°C ± 1°C

Counting of colonies

Examine the dishes under subdued light

The medium of the incubation: Plate count agar (PCA)

Composition of Plate count agar (PCA)

| Enzymatic digestion of casein : | 5.0 g |

| Yeast extract : | 2.5 g |

| Glucose, anhydrous (C6H12O6) : | 1.0 g |

| Agar : | 9g to 18g |

| Water : | 1000ml |

Methods of microbiological examination by East African Standard (EAS) 68-1 (2006), Part 1: Total plate count. This technique carried out at special laboratory.

Results

Kaolinite and talc are the principal minerals used for the Cosmetic creams powders and emulsions. Muscovite micas have long been used in eye shades and lipsticks for their high reflectance and iridescence, more recently, muscovite mica are added to moisturizing creams in order to produce a luminous effect on skin.

Kaolin is widely used as antidiarrhoeaics and also calcite features as antidiarrhoeaics. Iron titanium oxide is widely used as an antianemics because this mineral contains Fe2+ ions in its structure. Iron-titanium oxide is generally administered orally as a drink, but in severe cases it is administered parenterally.

Mineral supplements (calcite and magnesite) are administered in situations of physical weakness, convalescence, or asthenia in order to remedy slight deficiencies of essential ions, such as PO43−, Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, K+ and Fe2+.

Since the minerals, this conducted the study non-carcinogenic or toxic and what we were able through tests to prove that minerals under study conformed to international standards for minerals use in medicines and prescribed in British pharmacopeia (2009).

Even though some of the impurities found in the minerals under study, it can be controlled by reducing the dose or quantity added of the minerals on the drugs as stipulated in European Medicines Agency Pre-authorization Evaluation of Medicines for Human Use Doc. Ref. (2007).

After all this evidence we can now say that the minerals under study can be used in the pharmaceutical industries (drugs and/or cosmetics).

Discussion

Minerals used as active ingredients must be very pure in order to meet the strict chemical, physical and toxicological specifications set out in the European Pharmacopoeia (ph Eur) 2009; and United States Pharmacopoeia (USp) 2009.

After crushing and grinding samples, mineralogical analysis has been made of X-ray diffraction on these samples, which are needed to identify the minerals practically through the crystal structure the results were to prove the identity of the minerals.

The result of the X-ray diffraction of these samples as follows, graphite (graphite with a very little amount of quartz), ilmenite (ilmenite with a small amount of clinochlore), pyrolusite (pure pyrolusite), barite (pure barite), gypsum (pure gypsum), anhydrite (pure anhydrite), magnesite (magnesite with very little amount of dolomite & halite), dolomite (dolomite very little amount of calcite), limestone (pure calcite), fluorite (fluorite with a very little amount of quartz), talc (talc with a very little amount of montmorillonite & kaolinite), microcline (microcline with a very little amount of illite & albite), muscovite (pure muscovite), kaolin (kaolin with a very little amount of montmorillonite & quartz).

Therefore has been to move to the chemical analysis and of the major oxide, trace element, and rare earth's metals are required to prove the purity metals, where were the result of the purity of samples as follows, graphite (63.7%), ilmenite (68.6%), pyrolusite (65.7%), barite (64.6%), gypsum (93%), anhydrite (93.5%), magnesite (99.7%), dolomite (98.8%), limestone (100%), fluorite (65.2%), talc (71.7%), microcline (83%), muscovite (92.4%) and kaolinite (98.9%).

Now will concerns with chemicals specification that related to minerals solubility and pH of mineral solutions in framework of the comparison between standard pharmaceutical minerals and some Egyptian minerals samples (Tables 3, 4, 5 & 6) according to British pharmacopoeia (2009) and Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients (2009).

Table 3. Meanings of the terms used in statements of approximate solubilities.

| Descriptive term | Approximate volume of solvent in milliliters per gram of solute |

| Very soluble | Less than 1 |

| Freely soluble | From 1 to 10 |

| Soluble | From 10 to 30 |

| Sparingly soluble | From 30 to 100 |

| Slightly soluble | From 100 to 1000 |

| Very slightly soluble | From 1000 to 10 000 |

| Practically insoluble | More than 10 000 |

The term 'partly soluble' is used to describe a mixture of which only some of the components dissolve.

Table 4. Comparisons between solubility of standard pharmaceutical minerals and Egyptian minerals.

| Mineral Name | Standard solubility | Real solubility tests |

| Chare coal | Practically insoluble in all usual solvents | 0.1g in 1100 ml water |

| 0.1g in 1100 ml ethanol | ||

| 0.1g in 1100 ml benzene | ||

| 0.1 g in 1100 ml acetic acid | ||

| 0.1 g in 1100 ml sodium hydroxide | ||

| Ilmenite | Soluble in mineral acids; insoluble in water | 1 g in 20ml nitric acid |

| 0.1g in 1100 ml water | ||

| Pyrolusite | Freely soluble in water, practically insoluble in ethanol | 1g in 5 ml of water |

| 0.1g in 1100 ml ethanol. | ||

| Barite | Practically insoluble in water and in organic solvents. It is very slightly soluble in acids and in solutions of alkali hydroxides | 0.1g in 1100 ml water |

| 0.1g in 1100 ml benzene | ||

| 0.1g in 105 ml of dilute acetic acid | ||

| 0.1g in 105 ml of Sodium hydroxide | ||

| Gypsum | Very slightly soluble in water, practically insoluble in ethanol | 0.1g in 105 ml water |

| 0.1g in 1100 ml ethanol | ||

| Anhydrite | Practically insoluble in ethanol, slightly soluble in water more soluble in dilute mineral acids | 0.1g in 1100 ml ethanol |

| 0.5g in 55 ml water | ||

| 1g in 20 ml of nitric acid | ||

| Magnetite | Practically insoluble in water It dissolves in dilute acids with effervescence | 0.1g in 1100 ml of water |

| 1g in 20 ml of dilute acetic acid | ||

| Dolomite | Practically insoluble in water soluble in dilute acids with effervescence | 0.1g in 1100 ml of water |

| 1g in 20 ml of dilute acetic acid | ||

| Limestone | Practically insoluble in water It is very slightly soluble in acids and in solutions of alkali hydroxides. | 0.1g in 1100 ml water |

| 0.1g in 105 ml of dilute acetic acid | ||

| 0.1g in 105 ml sodium hydroxide | ||

| Fluorite | Soluble in water, practically insoluble in ethanol | 1g in 20 ml water |

| 0.1g + 1100 ml ethanol | ||

| Talc | Practically insoluble in dilute acids and alkalis hydroxide, organic solvents, ethanol and water | 0.1g in 1100 ml of HCl |

| 0.1g in 1100 ml sodium hydroxide | ||

| 0.1 g in 1100 ml benzene | ||

| 0.1g + 1100 ml ethanol | ||

| 0.1 g in 1100 ml water | ||

| Microcline | Freely soluble in water, very soluble in boiling water soluble in glycerol practically insoluble in ethanol | 1g in 5 ml of distillated water |

| 1g in 0.8 ml of boiling water | ||

| 1g in 20 ml of glycerol | ||

| 0.1g + 1100 ml ethanol | ||

| Muscovite | Freely soluble in water, very soluble in boiling water soluble in glycerol practically insoluble in ethanol | 1g in 5 ml of distillated water |

| 1g in 0.8 ml of boiling water | ||

| 1g in 20 ml of glycerol | ||

| 0.1 g + 1100 ml ethanol | ||

| Kaolin | Practically insoluble in water and in organic solvents | 0.1g in 1100 ml of water |

| 0.1g in 1100 ml of benzene |

Table 5. Comparison between acidity/alkalinity of standard pharmaceutical minerals and Egyptian minerals.

| pH of sample | Standard pH | Mineral Name |

| + | + | Chare Coal |

| 3.3 | 3 to 4 | Ilmenite |

| 5.2 | 5 | Pyrolusite |

| 3.5 to 8.5 | 3.5 to 8.5 | Barite |

| 7.3 | 7.3 | Gypsum |

| 10.4 | 10.4 | Anhydrite |

| 8 | 8.5 | Magnesite |

| 8.5 | 8.5 | Dolomite |

| 9.2 | 9 | lime stone |

| 5.9 | 5.0 to 8.5. | Fluorite |

| 7.2 | 7 to 10 | Talc |

| 3.5 | 3.0 to 3.5 | Microcline |

| 3.5 | 3.0 to 3.5 | Muscovite |

| 4.6 | 4.0 to 7.5 | Kaolin |

Table 6. Comparisons between microbial contamination of standard pharmaceutical minerals and Egyptian minerals.

| Minerals | Standard Total count/ gm | Real Total count/ gm |

| Graphite | ˂ 103 | 92 |

| Talc | ˂ 103 | 27 |

| Kaolin | ˂ 103 | 83 |

These minerals with a high sorption capacity and a large specific surface area can also function in pharmaceutical preparation as gastrointestinal and dermatological protectors, and anti inflammatories and local anesthetics, while water-soluble species can be used as homeostatics, antianemics and decongestive eye drops. Likewise, minerals with a high heat retention capacity can serve as anti-inflammatories and local anesthetics, minerals with high astringency are used as antiseptics and disinfectants and minerals which react with cysteine can serve as keratolytic reducers

On the other hand water-soluble species can be utilized in cosmetic product as ingredients in toothpastes and bathroom salts. Those minerals with a high sorption capacity and a large specific surface area can function as creams, powders and emulsions while minerals with proper hardness can act as abrasives in toothpastes. Highly opaque minerals and minerals of high reflectance are used in creams, powders and emulsions. Likewise, minerals with high astringency are included in deodorants.

Physicochemical Characterization

The therapeutic action is often correlated with the physical and physicochemical properties of the mineral; in other instances, it is related to the ionic composition of the mineral. In common with organic active ingredients, minerals in contact with the human body will pass through one or several of the following phases: liberation, absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion, which together are referred to by the acronym ‘LADME. The type and number of phases will depend on the nature of the mineral, the way of administration (oral, topical, Parenteral), and the kind of formulation (tablets, suspensions, powder, etc.).

Microbiological evaluation

The total viable aerobic count is not more than 103, 102, 103 micro-organisms per gram for graphite, talc, kaolin respectively. It is determined by using plate-count where the practical results are 92, 27, 83 by the same succession.

Conclusion

Some minerals that use in the pharmaceutical industry can be derived from Egypt. Large numbers of minerals are used in pharmaceutical industries as well as in cosmetic product. After selecting the minerals used in the pharmaceuticals industry and / or cosmetics and referred to in the constitutions of pharmaceutical products.

The author collects some representative samples of the minerals from the Egyptian desert after determining the whereabouts of the host rocks for the minerals through the work of geological maps show where their presence.

Some tests have been done on the 14 representing minerals graphite, ilmenite, pyrolusite, barite, gypsum, anhydrite, magnesite, dolomite, limestone, fluorite, talc, microcline, muscovite and kaolin.

After crushing and grinding samples, mineralogical analysis has been examined by X-ray diffraction, which are needed to identify the minerals practically through the crystal structure the results were to prove the identity of the minerals.

The result X-ray diffraction as follows graphite (graphite with a very little amount of quartz), ilmenite (ilmenite with a small amount of clinochlore), pyrolusite (pure pyrolusite), barite (pure barite), gypsum (pure gypsum), anhydrite (pure anhydrite), magnesite (magnesite with very little amount of dolomite and halite), dolomite (dolomite very little amount of calcite), limestone (pure calcite), fluorite (fluorite with a very little amount of quartz), talc (talc with a very little amount of montmorillonite and kaolinite), microcline (microcline with a very little amount of illite and albite), muscovite (pure muscovite), kaolin (kaolin with a very little amount of montmorillonite and quartz).

Chemical analysis of major oxides, trace elements, and rare earth's metals are required to prove the purity metals, where were the result of the purity of samples as follows, graphite (63.7%), ilmenite (89.75%), pyrolusite (65.7%), barite (64.6%), gypsum (93%), anhydrite (93.5%), magnesite (99.7%), dolomite (98.8%), limestone (100%), fluorite (65.2%), talc (71.7%), microcline (83%), muscovite (92.4%) and kaolinite (98.9%).

As well as solubility tests, pH meter and total dissolved salts, loss on ignition and some chemical reactions are compared with results the tests referred to in the British Pharmacopoeia.

Test was conducted atomic absorption spectroscopy to ascertain the extent of the potential mineral solubility in solvents referred to in the constitutions of drugs to iron oxide minerals which were identical one hundred percent in its solubility to the reference samples.

The analysis was performed infrared for some minerals to ensure their conformity with the analysis in hand bock of pharmaceutical excipients, which represents a sign of recognition for the minerals and the degree of it's purity where, infrared (IR) spectrum was registered on Nicollet 6700 FT-IR spectrometer with the “Smart Split Pea” diamond micro-ATR accessory. ATR-correction was carried out; the result was identical to the degree of the above purity.

Finally, microbiological analyses are in kidney-microbial count to three minerals, graphite, talc and kaolin. These analyses determine that the count does not increase kidney microbial colonies about 103 colonies to use metal medicines.

The results were the process to make sure that the count kidney much less where it was 92 graphite, 27 for talc, and 83 of the kaolin.

So we can say with confidence from the possibility of using these metals held by the experiments and that collected from Egyptian deserts in pharmaceutical industries and cosmetics.

What to get us to the work of some drugs and cosmetics from these minerals to prove what we say in practice.

Future developments would include purification (e.g., elimination of potentially harmful trace elements), laboratory synthesis of selected minerals, delamination of clay minerals, and preparation of nanosize mineral particles. The overall aim is to obtain minerals of high purity with controlled particle size and shape, enhancing its physical and physico-chemical properties.

Egyptian pharmaceutical minerals have the same comparable physicochemical properties to that of commercial brand.

Acknowledgments

The author is deeply indebted to Prof. Dr. Ahmed El-Mezayen, Geology Department, Faculty of Science, Al-Azhar University for the guidance of good and many of the conversations with insight during the development of these ideas and comments to help complete this text.

The author also thanks Prof. Dr. Gehad Mohamed Saleh, Professor of Economic geology, Head of Isotope Department at Nuclear Materials Authority for providing the chemical analyses for the present study.

References

Abdel-Aal EA. 1995. Possibility of utilizing Egyptian ores for the production of magnesium oxide by acid leaching. Fizykochemiczne Problemy Mineralurgii, 29: 55-65.

Abdel-Aziz YM. 2001. Manganoan ilmenite from the gabbroic rocks of Abu Ghalaga area, Eastern Desert, Egypt. The 2nd international conference on the geology of Africa. I: 101-111, Assiut, Egypt.

Abd El-Wahed AA, Sadek AA, Abdel Kader Z, Motomura Z, Watanabe K. 2007. Petrogenetic relationships between pegmatite and granite based on chemistry of muscovite in pegmatite wall zones, Wadi El-Faliq, Central Eastern Desert, Egypt. Annals Geol. Surv. Egypt. V.XXIX, P. 123-134.

Akaad S. Abdallah AM. 1971. Contribution to the geology of Gabal Ataqa area. Ann. Geol. Survey. Egypt, 1: 21.

Ali-Bik MW, Taman Z, El-Kalioubi B, Abdel-Wahab W. 2012. Serpentinite-hosted talc–magnesite deposits of Wadi Barramiya area, Eastern Desert, Egypt: Characteristics, petrogenesis and evolution. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 64: 77-89.

Amer AM. 2010. Hydrometallurgical processing of low grade Egyptian magnesite. Physicochemical Problems of Mineral Processing, 44: 5-12.

Aref MAM. 2000. Halite and Gypsum morphologies of Borg El-Arab solar salt works-A composition with the underlying supratidal Sebkha deposit, Mediterranean coast, Egypt. Proc 5th internat. conf. on Geol Arab world, Fac. Sci., Cairo Univ., Egypt, 3: 47-51.

Awad NT. 1995. Distribution of trace elements in some Egyptian fluorites with particular reference to REEs. Egyptian Mineralogist, 7: 33-45.

Baioumy HM, Gilg HA, Taubald H. 2012. Mineralogy and Geochemistry of the Sedimentary Kaolin Deposits from Sinai, Egypt: Implications for Control by the Source Rocks. Clays and Clay Minerals, 60(6): 633-654.

Basta EZ. Saleeb WS. 1971. Elba manganese ores and their origin, South-eastern Desert, U.A.R. Mineralogical Magazine, 38: 235-44.

British Pharmacopoeia, 2009. Crown Copyright 2008. Published by The Stationery Office on behalf of the Medicines and Healthcare products.

Carretero MI. 2002. Clay minerals and their beneficial effects upon human health. A review. Applied Clay Science. 21(3–4):155–163.

Doc. Ref. London. 2007. European Medicines Agency Pre-authorisation Evaluation of Medicines for Human Use CPMP/SWP/QWP/4446/00 corr.

East African standard EAS. 2006. Milk and milk products, Methods of microbiological examination, Part 1: Total plate count.

El-Mansi MM. 2000. Coloration of Fluorite & its relation to radio activity, Egypt mineralogy, mineralogy Soc, Cairo, 12: 93-106.

El-Mezayen AM, Amin BE. 1995. Geological, petrographical and geochemical studies on the ultramafic rocks- mélange and associated graphite of Abu Quraiya area, Eastern Desert, Egypt., Al-Azhar Bull. Sci., 1: 741-761.

Gomes CSF, Pereira Silva JB. 2006. Minerals and Human Health. Benefits and Risks. Centro de Investigação«Minerais Industriais e Argilas». Fudação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia do Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior. Aveiro (Portugal).

Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients, 2009. Published by the Pharmaceutical Press, An imprint of RPS Publishing 1 Lambeth High Street, London SE1 7JN, UK 100 South Atkinson Road, Suite 200, Grayslake, IL 60030-7820, USA and the American Pharmacists Association 2215 Constitution Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20037-2985, USA.

IMA Europe, 2014. Industrial Minerals Applications. Your world is made of them. Pharmaceuticals & Cosmetics.

Ismail MM. El-Mahdy OR. El-Nozahi FA. 1974. Geological studies of Gabal Ataqa surface section. Part I. Bull. Inst. Desert Egypte, 24: 11.

Kamel OA, El-Bakry A, Attia GM, Gharib ME. 1999. Mineralogy, mineral chemistry & geochemistry of Rod Um El-Farag granitic pegmatites, Eastern desert, Egypt, El Minis Sci Bull, Minia Univ, 12(2): 64-88.

Lefort D, Deloncle R, Dubois P. 2007. Les minéraux en pharmacie. Géosciences, 5: 6–19.

López-Galindo A, Viseras C, Cerezo P. 2007. Compositional, technical and safety specifications of clays to be used as pharmaceutical and cosmetic products. Applied Clay Science, 36: 51–63.

Moharram MO. 1959. Main mineral deposits produced in Egypt, Geol Surv Egypt, Cairo, Egypt, Rep, p 21.

Mondo Minerals. 2014. Talc Applications. Talc for Pharmaceuticals.

Nichols HW. 1906. Sand-barite Crystals form Oklahoma: Geol. Pub. Field Columbian Mus, 3: 31.

Ragab AI, Bishady AM. Shalaby SH. 1983. Contribution to the petrography of the granitic rocks of Gebel El Delihimi stock, Eastern desert, Egypt, 21st Annul Meet Geol Soc, p.25.

Rumble D. 1976. Thermodynamic analysis of phase equilibria in the system Fe2TiO4-Fe3O4-TiO2. Carnegie Inst. Washington Yearb, 69: 198-207.

Schandl ES, Gorton MP, Wasteneys HA. 1995. Rare earth element geochemistry of the metamorphosed volcanogenic massive sulfide deposits of the Manitouwadge mining camp, Superior Province, Canada: a potential exploration tool? Econ. Geol, 90: 1217-1236.

Shead AC. 1923. Notes on Barite in Oklahoma with chemical analyses of Sand Barite Rosettes: Okla. Acad. of Science, 3: 102.

Surour AA. 2001. Fluid inclusions, distribution of rare and genesis of Abu Gerida fluorite mineralization, Central Eastern Desert, Egypt. 5th Inter. Conf. On Geochemistry, Alex. Univ., Egypt, 12-13: 353-371.

Tolbert GE. 1979. Assessment of energy related minerals commodities in Egypt, Joint Egypt, USA Rep, Egypt USA Cooper Energy Assess, 2: 165-184.

United States Pharmacopeia (USP) 32–NF27. This product is current from May 1, 2009 through April 30, 2010.

Viseras C, Aguzzi C, Cerezo P, Lopez-Galindo A. 2007. Uses of clay minerals in semisolid health care and therapeutic products. Applied Clay Science, 36: 37–50.

Zaghloul ZM, Yanni NN, Samuel MD, Guirgues NR. 1982. Characteristics and industrial potentialities of kaolin deposit near Abu Darag, Gulf of Seuz. Desert Inst. Bull., A.R.E., 32(1-2):19-45.

Zaki RM. 2005. Geochemical characteristics and element association in different rock types of El Minia District, North Upper Egypt sedimentology Soci Egypt, Sediment, Cairo, Egypt, 13: 34-370.

Zatout MA. 1974. The dolomite and dolomitic rocks of Gabal Ataqa. Geol. Surv. Egypt. p. 27.